In acquiring land on the public domain, how were the Indian Homestead Act and General Allotment Act Section 4 different?

Eligibility was one difference. Under the General Allotment Act, only those who were “not residing upon a reservation, or for whose tribe no reservation has been provided” could apply for an allotment on the public domain. With few reservations in the state, most California Indians were eligible for a Section 4 allotment. However, a resident of the Hoopa reservation, for example, was not.

The Indian Homestead Act of 1884 was more liberal in its eligibility. “Such Indians as may now be located on public lands, or as may, under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, or otherwise, hereafter so locate” could apply for a homestead. Because the law was blind to an individual’s reservation status, even a resident of the Hoopa reservation qualified for homesteading.

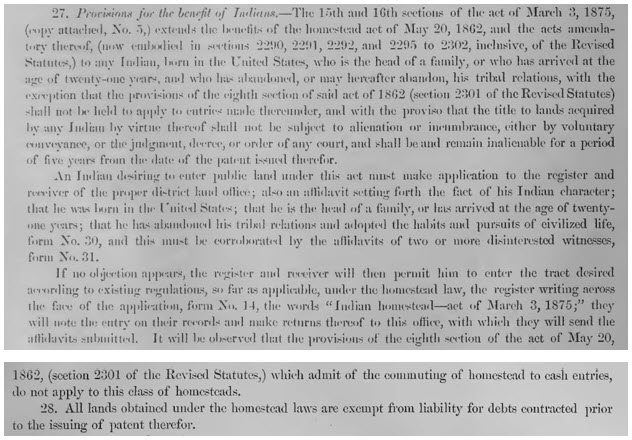

Another difference involved the application process (which changed over time; these comments focus on the early years). The General Land Office circular of 1877 outlined the early Indian homesteading procedure (see header image). One had to apply at the land office and provide affidavits of two witnesses, live on the land for five years, and then “prove up” at the land office with two witnesses. Initially the Indian Office was not involved, but by 1889 the instructions had changed to also require a “certificate from the agent of the tribe to which [the applicant] belongs.”

Regulations governing the application process for Dawes Act Section 4 allotments on the public domain were issued by the Interior Department on September 17, 1887. One had to apply at the land office and provide affidavits of either two witnesses or an Indian agent. The allottee did not need to prove up. Thus, allotments required less travel to the land office, less paperwork, and generally less bureaucracy.

How soon a trust patent was issued seems to be a third difference. As far as I can tell, an Indian homesteader only received a trust patent when he proved up five years after making entry. An allottee got a trust patent much sooner, after his allotment application was processed in Washington. The Indian homesteader’s five-year long road to a trust patent might have left his homestead less secure from whites ready to seize it and dispossess the homesteader or otherwise contest his entry before the trust patent was issued. The Indian Office’s annual reports from the 1890s note that such contests were not unusual, with Indian homesteaders (and allottees) not knowing how to defend title nor able to pay legal fees and thus losing their land. In many other cases Indian homesteaders did not prove up, so the land office canceled their entry and their land was lost. Of course, having a trust patent was hardly ironclad protection from encroachment.

Finally, a major difference involved the government’s investment in implementing the Dawes Act, which seems to have exploited unused funds set aside for Indian homesteads. Under the Act of March 3, 1891 (26 Stat. 989), the Interior Department was allowed to use the balance of the fund titled “Homesteads for Indians” to employ allotting agents dedicated to Section 4 allotment work. That year the Indian Office began sending allotting agents to California, where they churned out two thousand allotments on the public domain under Section 4 of the General Allotment Act before Kelsey began his California work.

So, Kelsey was substantially correct in writing that the Indian Homestead Act was little used in California because “the technical requirements were too onerous, no one was designated to see that Indians were assisted and few Indians ever heard of the Acts” (“Mr. Kelsey’s Brief History of the California Indians” in Warren K. Moorehead, The American Indian in the United States, 333).