In his 1906 report, Kelsey noted that 2,058 allotments had been made by allotting agents in California beginning in 1891. He could provide an exact number because separate books were maintained to track Indian allotment applications. Indian homestead applications were not tracked the same way. Instead, they were mixed in with all the other homestead entries in register books. Though lacking a precise number, Kelsey found few Indian homesteads in California.

Given the low number of Indian homesteads in California, perhaps it is no surprise that some were handled incorrectly. The Indian homestead patents in the BLM General Land Office Records database show various discrepancies and mistakes made by workers implementing the law.

For example, Charles Peterson is listed in the database as having received an Indian Homestead Fee Patent (12 Stat.392) to land in Fresno and Tulare Counties in 1871. How is this possible when the first Indian Homestead Act was not passed until 1875? I can only guess without access to Peterson’s land entry file at the National Archives. There was a provision allowing homesteads for the Stockbridge Munsee of Wisconsin in the 1865 appropriations act for the Indian Office (13 Stat. 562), and an Interior Department circular of April 1, 1870, allowed Indian homesteads on public lands until 1874, when the circular was rescinded and all such homesteads ordered to be cancelled. Neither of these seem to fit this situation. It may be that Peterson applied as a citizen who had dissolved his tribal relations and the land office accepted his status.

In 1920 John Campbell was issued a new patent for his land in Inyo County under the Act of March 3, 1875. It replaced his 1892 patent, which was “erroneously issued under the Act of July 4, 1884.” Citing the first Indian Homestead Act as the proper authority despite the second Indian Homestead Act being in effect is mystifying. Perhaps Campbell made his entry before July 4, 1884, so the 1875 law was the only law in effect and thus considered the valid authority.

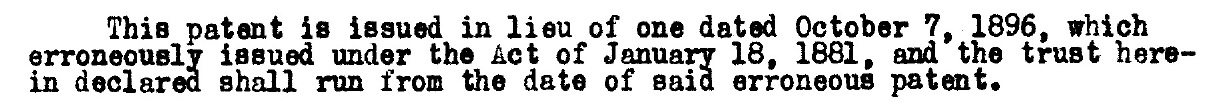

In the 1890s, the patents of both Ulsha or Mack in Fresno County and Chico Jim in Plumas County were “erroneously issued under the Act of January 18, 1881.” The 1881 act (21 Stat. 315) was a special act that applied only to the Winnebagos of Wisconsin. New patents citing the Indian Homestead Act of 1884 were issued to the two homesteaders in the 1910s, with the trust period running from the date of the erroneous patent.

The 1890 patent of William Wallupie in Amador County was “canceled because it erroneously issued under the Act of May 20, 1862.” This was the original homestead act for U.S. citizens. He received a new trust patent in 1911 under the Indian Homestead Act of 1884.

Two Paiutes with homesteads in Shasta County, Edna Button, heir of Billy Button, and Charley Green, were issued new patents on the same day in 1919. The new patents were issued “in lieu of one which the trust period has expired.”

As these examples show, administering the Indian Homestead Act was confusing for federal workers, who only occasionally dealt with the law and were probably unfamiliar with it. This would have made the homesteading process even more confusing and difficult for the native applicants the law was intended to benefit. The situation only worsened as more public land laws were enacted, including the laws governing homesteading in the burgeoning national forests in California.