His wife feared he would die of cancer, but instead Kelsey had a heart attack. He died on July 3, 1936, at age 74, after collapsing while locked in the bathroom at his home in Vista. One of his young nephews broke through a bathroom window and unlocked the door from inside. Kelsey’s body was cremated and shipped to the Kelsey family plot in Geneseo, New York.

Kelsey was a regular pipe smoker. He had a growth removed from under his tongue and quit the pipe before he took a job as land agent with the Southern Pacific Company in 1918. When he applied for the job Kelsey downplayed his condition, noting that “the doctors are by no means agreed that the ulcer removed from my tongue was cancerous.” Three years earlier Kelsey wrote to Matthew K. Sniffen from Yosemite about an unnamed medical problem that might be this surgical procedure: “I have so far discovered no sign of recurrence of my trouble, though my vitality is doubtless somewhat depressed, showing itself chiefly by subnormal temperature. My physician has sent me to the mountains to build me up, I suppose, so I could stand a better show should there be a recurrence.”

I was not able to obtain Kelsey’s death certificate. When I requested it from California’s Office of Vital Records some twenty years ago, they sent me the death certificate for Charles Henry Kelsey. After I followed up on the error, they sent me a “Certificate of No Public Record” for Charles Kelsey. It stated that they searched for a record of his death in the Statewide Index for the period from July 1905 to the present (“the present” being September 24, 2002) but did not find it.

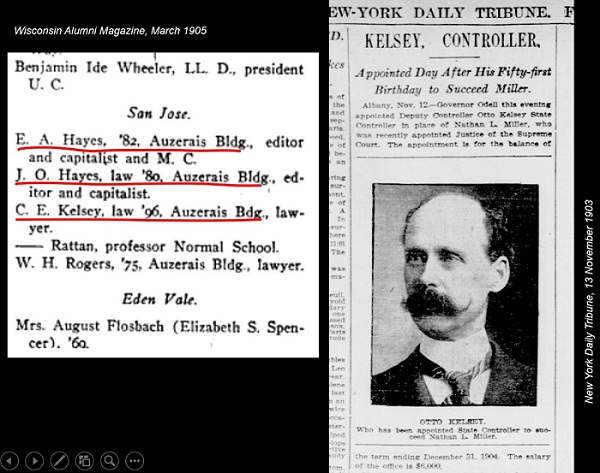

The only obituary I’ve found for Kelsey is from the University of Wisconsin’s alumni magazine for March 1937. An image of it heads this piece. I sometimes wonder why Kelsey’s family seems to have chosen not to announce his death to the many people in California who knew him.