Fundraising was always a challenge for the Northern California Indian Association (NCIA). Cornelia Taber wrote Albert K. Smiley in 1909 that “California has always been slow to respond to Indian appeals.” The NCIA repeatedly noted its outsized reliance on donations from the east coast, with Taber acknowledging at the Commonwealth Club, “We have had a great deal of help from the East, but they are telling us what is perfectly true: California ought to take care of her own.”

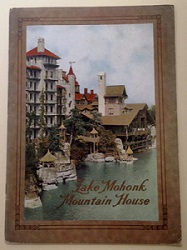

As part of the National Indian Association, the NCIA had access to a large network of supporters and could appeal to sister branches in eastern cities. Far removed from the field of work and having larger memberships, these eastern branches were primed to support mission activities beyond the Mississippi. As a whole, the national association directed its resources to the west, with California its “most active field,” according to Valerie Sherer Mathes in The Women’s National Indian Association: A History (p. 35). In addition to this built-in structure, NCIA leaders also had personal connections in the east. Anna and Cornelia Taber were migrants from the New York City area and stayed in touch with friends and fellow Indian reformers back home. Among their contacts were the Smiley brothers, who sponsored the prestigious Lake Mohonk Conference of Friends of the Indian, where the Tabers were always welcome. The Tabers used their contacts to network and open doors to potential donors. Much of the funding for the NCIA’s industrial school at Guinda was secured by Cornelia Taber and others from eastern sources.

Frederick G. and Beryl Bishop Collett’s Indian Board of Co-Operation (IBC) coexisted with the NCIA in the Bay Area in the 1910s, so it experienced the same fundraising challenges. Adding to the challenge was a fundamental structural difference between the two groups. While the NCIA was run largely by volunteers who had other sources of income, the Colletts sought to make their living as salaried employees of the IBC. In the beginning their efforts fell far short of their target. In their early reports the Colletts often lamented their time and effort spent on raising money and suggested various methods to offload fundraising to others.

As an independent organization, the IBC had no network of eastern affiliates at hand. Like the Tabers, Frederick Collett was from New York, as Timothy Wright describes in his M.A. thesis, “‘We Cast Our Lot with the Indians from that Day On’: The California Indian Welfare Work of The Reverends Frederick G. Collett and Beryl Bishop-Collett, 1910 to 1914.” However, Frederick Collett’s origins on an upstate farm did not provide the same connections to easterners of wealth and those active in the Indian reform movement. He never attended the premier annual gathering of Indian reformers at Lake Mohonk. Collett went east to raise funds in 1915, but I have yet to find a report of the results. To raise money the Colletts spoke at conferences and conventions of religious organizations, paid visits and wrote letters to wealthy individuals, and sent mass mailings of publicity materials. They also sought funds in the western states outside California, in Portland, Seattle, and Salt Lake City. Always enterprising, Collett brashly submitted a bill for his services in securing a school building for the Indians at Hopland to the superintendent of schools at Ukiah, Anna Porterfield, in 1915. Not surprisingly, Porterfield refused to pay.